I direct plays for a living and have earned some portion of my annual income doing so for over twenty years. Anyone who has worked with me in at least the last decade or so has likely heard me rail against the sublimation of the other. This is an academic-y way of saying that I am *typically not a fan of taking someone with a marginalized identity and layering another form of masking/erasure/marginalization on top of that. Think of casting Black actors to play Gremlins (especially the after-midnight variety), or think about the casting of Orcs in the LOTR films. Think about Caliban in Shakespeare’s The Tempest as a Black, Indigenous, North African, Middle Eastern, Latiné actor being cast to only then be given fins, or paws, or a tail, or be covered in fur, or painted green. So yeah, I’m not with it.

Because of this, I had very true and deep concerns about seeing the film adaptation of Wicked. I love the musical and have since it played San Francisco in its pre-Broadway nakedness in 2003. I have always identified with Elphaba (ooooh L. Frank Baum might be rolling in his grave). I had never needed a Black woman under the makeup for the character to resonate so deeply for me. I certainly don’t think Gregory Maguire or Stephen Schwartz were thinking of the plight of Black women or women of color in general when they penned their respective versions. That didn’t matter because I understood feeling misunderstood, being mocked, laughed at, underestimated, and “I’m through accepting limits, ’cause someone says they’re so,” was a battle cry the moment I heard it. I was worried about what it might mean to put a Black woman under all that paint, to cast an actor with Dwarfism and then hide him by making him a CGI goat, or casting an actor who uses a wheelchair to play a character that aligns with the *oppressor. With so much sublimation of other happening I was nervous I wouldn’t like the film. That it would traffic in age-old tropes, erase the lived experiences of already marginalized folks, and genuinely fuck up a property that I love so wholeheartedly.

And yet, these actors deserve opportunities to play complex, contradictory, imperfect characters: villains, superheroes, professors, goats, and wicked witches. They deserve the dramaturgy of Sankofa, to “go back and get it;” to see themselves in fantasy worlds, in lands of talking lions, tinmen, and dancing scarecrows. They deserve pasts, presents, futures. The 1939 Wizard of Oz film (from which Maguire draws his inspiration) didn’t create space for the boundless talent of actors of color, the actors with Dwarfism in that film were relegated to playing munchins, and though the film left a number of its stars with disabilities, actors with known or visible disabilities weren’t cast. That film was produced under a strict Hays Code Hollywood and I wasn’t sure if, in paying homage to that film, Wicked would perpetuate similar harms while patting itself on the back for diverse casting as so often happens when bodies of marginalized folks are used but not cared for.

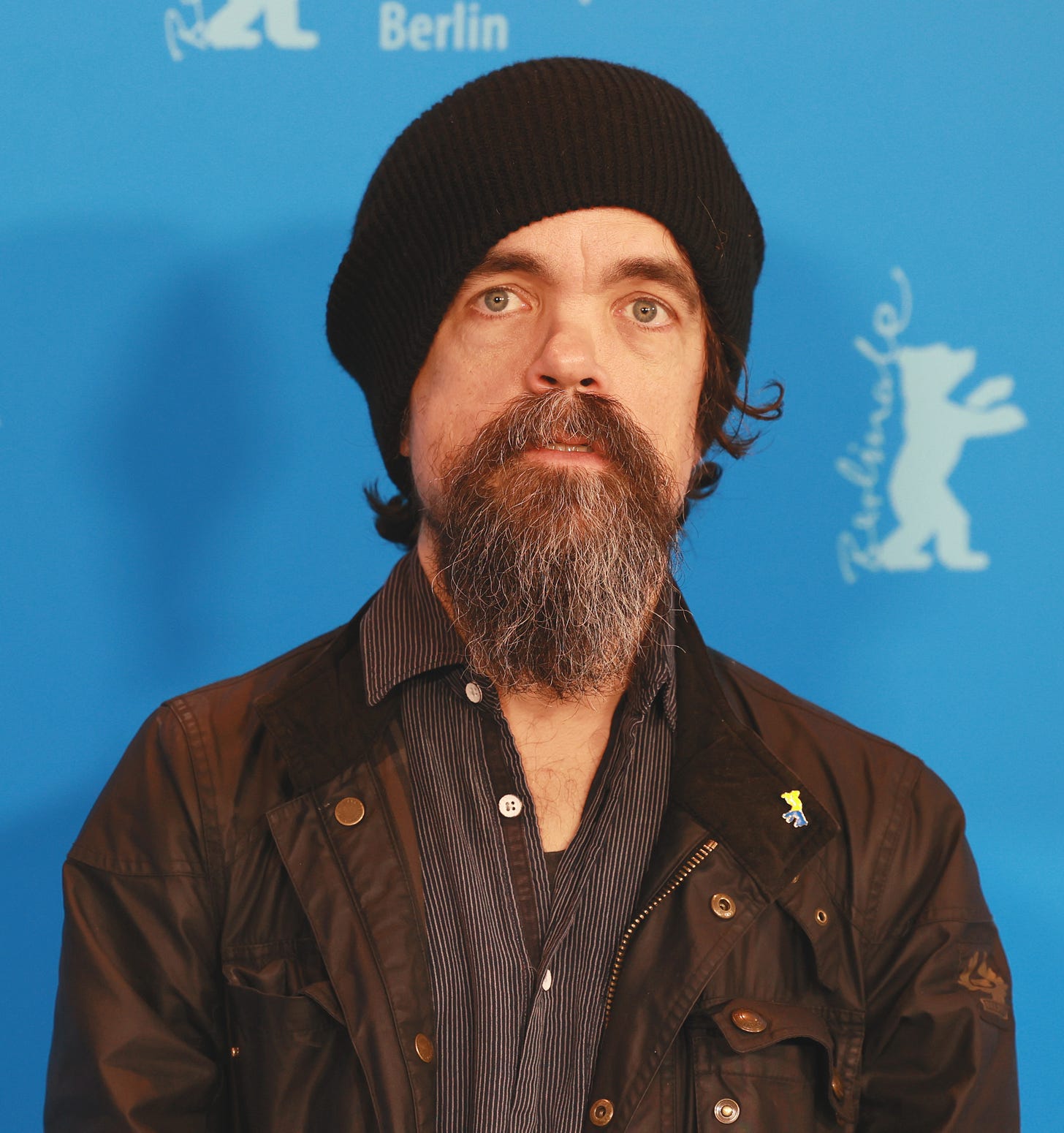

Instead, I found Wicked spectacular in every way. Peter Dinklage was not the only actor with Dwarfism, and they didn’t all play munchins, Marissa Bode was not the only actor to use a wheelchair. There were actors of all varieties playing characters along the full spectrum of thought and deed. I loved it. I was happy. I thought the cinematography was stunning, the production design fabulous, the choreo was fire. Jon Chu was in his bag with this one with thoughtful and intentional choices that made these the absolute most necessary actors to tell this story at this moment.

So Dawn, why the think piece? Well, what I am taken by is the discourse that now exists around the film. People arguing that they *made it political. One, all theatre/film/music/art is political. It is of and concerning a people, people constitute the politic. Like, duh. I am taken by the fact that people would refer to Cynthia as a diva when she speaks of the erasure she felt looking at a fan edit of the poster. She was erased. Perhaps the fan meant no malice, and yet Cynthia’s very striking Black British features were obscured in the edit. Then I am taken by how many Black women are feeling affirmed and how many non-Black people are clocking the allegory in light of our current socio-political climate. I was not expecting that. I was not expecting to feel it as any more timely than I did any of the times I saw the stage show. Or to feel any more affirmed than I’ve always felt by the show, any more than I feel affirmed by “Waving Through a Window” from Dear Evan Hansen or “Breathe” from In the Heights even though I am not a teenage white boy with a single mom or a Puerto Rican woman who grew up in NYC. Perhaps because I have lived with the musical for twenty years? Perhaps because when Idina, or Eden, or Mandy, or Stephanie, or Christine Dwyer sang the role of Elphaba I already saw myself in the role? Perhaps because when I saw it on London’s West End the actor playing Elphaba was Black? What I know is that sharing it with all of you at once on such a megascale has made it feel like a once-in-a-generation experience.

I was so deeply moved and I expect to use the film as a teaching tool for years to come. The soundtrack is on repeat and there is a countdown timer to part two active on my phone. Cynthia Erivo is a PHENOM. Her take on the role is singular, and because it is the film version it is now immortalized. I also thought Ariana Grande slayed (do not @ me). The whole cast was fantastic. So yes, Black women should get to play Elphaba. Yes, Black women should star in fantasies. And yes, Black women should get to play green characters. What I want to know though is, can you see me if I’m not green? Why can’t a Black woman express her anger, rage, hurt, truth? Why can’t someone with Dwarfism tell you if they are feeling silenced or erased? Why can’t you listen when the person using the wheelchair tells you they would rather you not push their chair uninvited? Why do humans need so much allegory (green women and goats) to face the realities of the harm we cause one another every day?

Do we feel better about the abuse imparted on Caliban if we see him as less than human? Shakespeare knew he’d need allegory to get passed the censors, a window into a world to appeal to those who didn’t want to hold a mirror up to themselves. Shakespeare puts these lines in Hamlet’s mouth, “What’s Hecuba to him or he to Hecuba / That he should weep for her?,” as a way to interrogate how characters onstage (onscreen) can garner our empathy. And Shakespeare also reminds us, “The play's the thing, wherein I'll catch the conscience of the king.” Did Wicked catch our collective conscience? Have we interrogated why we wept for her? Do we believe “we have been changed for the better”? Did we learn something and will we be changed “For Good”?